You think you’re immune, until you discover you aren’t.

In February 1995, god that’s nearly thirty years ago, I grew up in a hurry. Or at least my budding work persona did. I was one of five wide-eyed geology students freshly fallen from the Ontario turnip truck in the early weeks of eight month, co-op, work terms at Gulf Canada Resources in Calgary. For most of us, it was our first time in the gilded, Prairie oil capital. For a couple of us, it was also our first experience in a “big” city. For all of us, it was our first work experience in the oil patch.

Gulf Canada had a storied history in Alberta’s oil patch, stretching back to its very beginning, but in recent times was a struggling, wounded shadow of its former self having been ravaged by mismanagement under the O&Y real estate empire in the late 80s and early 90s.

After bankruptcy proceedings, Gulf ended up in the possession of major banks. These banks, hoping to turn a woeful Gulf around and salvage some value from their ill-fated commercial real estate loans, brought in a group of fast-drawling Texans (think Jerry Jones as a Pixar villain) to work some lone star magic. With bolo ties swaying and spurs rattling, the Texans settled into their offices and like barbed wire ripping through exposed flesh, fired half of Gulf’s workforce.

Watching People Lose Their Job

Having grown up in Southern Ontario, I was peripherally familiar with seemingly annual auto industry layoffs and re-hirings, but I’d never witnessed it firsthand. My hometown had a stable corporate employer and the prospect of hundreds of people losing their livelihood was, by and large, foreign to me. This was quite a shock.

It also caused unexpected panic. Would we five co-op students be safe from the cuts? Would our contracts be honoured or would we suddenly find ourselves jobless for the final eight month work term of our university careers, a daunting possibility both financially and academically.

Word eventually came that our contracts would, indeed, be honoured making us the only five Gulf Canada Resources employees guaranteed to retain our jobs. Well, us and the Texans. This news was at once a relief but also a heavy burden as hundreds of strangers and new friends had their lives thrown into chaos in our worry-free midst.

The day the layoffs happened, I sat alone in my office, silent, watching broken and sometimes weeping people pack their belongings into boxes before shuffling, zombie-like, to the elevator banks. I remember feeling a cold steeliness envelope my spine, as if my body was armouring itself to these callous realities of adulthood and the career awaiting me after graduation.

By late 1998, almost four years later, I was again employed at Gulf Canada Resources. The Texans were gone, having worn out their welcome with magic that failed to impress but Gulf remained alive. It was very different from the one I knew in 1995, though. No longer teetering on the edge of insolvency, Gulf remained vulnerable to oil price shocks thanks to an excessive debt load incurred via several takeovers. Banks never learn.

Despite the vulnerability, Gulf was strong enough earlier that year to be hiring new technical staff, of which I was one. I left my job in Saskatoon, relocated to Calgary, and eagerly began what I envisioned would be a lifelong career as an oil and gas geologist. But by year’s end, the vagaries of international oil pricing turned decidedly sour and like a recurring nightmare, a mere eight months after my hiring, layoffs were announced.

This time I would face the knife as an employee rather than a summer student. Whatever sympathy that summer student contract afforded me in 1995 had vanished the second a framed degree went up on my office wall. These layoffs could easily cut my oil and gas career abruptly short. And right before Christmas, no less. How’s that for a bitter welcome to a big boy pants world?

Thankfully, luckily, I survived. But once more I would watch as many more people packed those same boxes and shuffled off to that same elevator bank. Dead men, and women, walking. The armour around my spine thickened and stiffened.

Effective work is all but impossible in the hours after pink slips have been delivered, so we all escaped to a pub on the main floor of the Gulf office tower and smothered our stress and fear with drink long into the evening hours. Emboldened by intoxication, I returned to my office to retrieve my jacket and bag and took a moment to email “Gulf All World” a newspaper clipping where a rival oil company’s CEO stated that he was going to cut manager salaries rather than fire people. Or something to that effect, my memory is foggy on the details. He felt it was better in the long term for both staff and company alike, rather than endless cycles of hiring and firing.

The internet was still young and you could get away with naive stunts like that. I received a mild chastisement from the senior area manager when those of us left returned to work the next morning. My friends thought it was funny. And bold. Life went on.

The First Time I Got Fired

It continued for a grand total of two months, when in February of 1999, oil prices having continued their slide to jarring lows, yet another round of layoffs were announced. Third time’s the charm, as the saying goes, but that charm isn’t necessarily good. This time, almost five years to the day after I first witnessed a mass layoff, I finally found myself packing those same boxes and making that dreadful walk to that same elevator bank.

Witnessing other people get fired, no matter how many times, won’t properly prepare you for when it happens to you. It’s just an awful experience. Your ego is instantaneously crushed while a flood of churning emotions invades your vulnerable psyche. It’s like a spotlight is suddenly cast upon you stumbling around the stage desperate to remember your lines. Many others are doing likewise. Everyone else awkwardly trying to comfort you with poorly suppressed visages of relief upon their faces.

I’ve seen layoffs implemented a few different ways now, and everyone has an opinion on each method’s propriety, but there just isn’t a good way to fire people in these situations. That being said, some are certainly worse than others. Mine was perhaps one of those.

At Gulf, we worked in those impersonal cubicles of corporate lore. The day prior, we had been told to arrive the next morning and immediately go to our cubicle and await a potential phone call with further instruction. If you received such a phone call, you were directed to one of the enclosed, glass conference rooms where your supervisor and a human resources representative were waiting to deliver the news that the picturesque, sweeping mountain tunnel you thought your career path was on, was, in fact, painted on a cliff face by the Road Runner and you had just become Wyle E. Coyote.

I sat down in my cubicle. I nervously fiddled around on my computer. My mind cycled through fear, resignation, optimism, and indignation as the ringing telephones erupted methodically around me like funeral bells tolling. After each ring, a head would pop above the cubicle walls like a ragged gopher in a derelict carnival game.

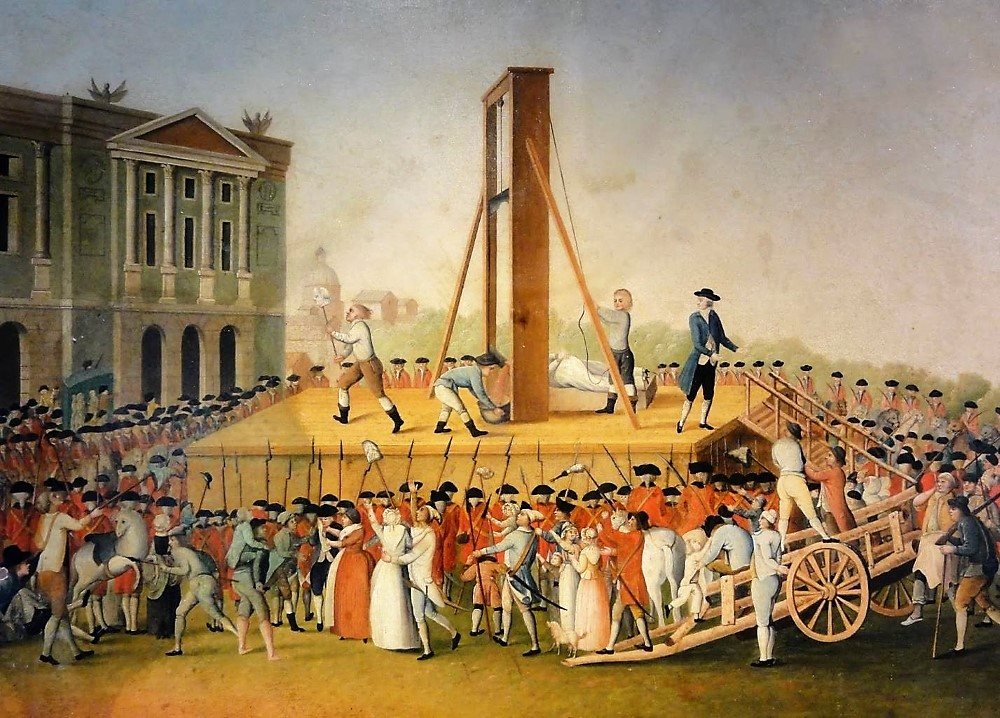

This continued for quite some time. Long enough that I allowed myself to begin thinking I might once again, just maybe, avoid the carnival-goer’s mallet. But soon the damning red light on my phone blinked followed by the ring beckoning me to the gallows.

I was 27 years old, a mere ten months into this new career I was so excited to begin. The first thing I had done after moving to Calgary was purchase a home. I used all my meager RRSP savings for a First Time Home Buyers loan to get a down payment and then proceeded to max out my pre-approved mortgage. It was a stupid thing to do. Now that I’d lost that job less than a year later, the degree of stupidity became crystal clear. So this is what panic feels like.

Despite the swell of emotion gripping my being, the one thing I remember most vividly was how distressed my normally unflappable boss was when he fired me. He had limited input on who was kept and who was turfed, a time-honoured cowardice in the oil patch where upper management makes decisions over people’s lives and then tab mid-tier managers to do the deed. He was outwardly emotional and suffering. I remember having to specifically say to him that I would be okay. It was such a strange experience, feeling compelled to console the very person tasked with thrusting my life into disarray.

I returned to my desk. There’s an odd sense of peace that overcomes you at that moment. The finality of it, of knowing it is over, is strangely comforting. I imagine this is not unlike the final thought before one dies. But it’s a brief moment of comfort and soon the emotional turmoil returned along with an injection of adrenaline. I packed up my belongings and made my way to the watering hole on the main floor of the building and got shit-faced.

It was an epic afternoon. All my coworkers were there, those that had been fired like me and those that had survived. Our bosses were there too, many opening up bar tabs. They too needed a release. Later, more friends would arrive from their jobs and join the party as the work day came to a close. It was an all-out wake for yet another sad lot of former Gulf employees. It was, and remains, one of the greatest blowouts of my life.

That night, the crowd of revelers, incapable of consuming another drop, slowly thinned into nothingness as reality reasserted its control over our lives. I solemnly stumbled into a cab, returned to the money pit of a house I no longer knew how I would pay for, collapsed into the lap of my girlfriend on my bed and sobbed.

The days and weeks that followed were somewhat surreal. I took in a couple roommates, one an old university friend, the other a sister of a good friend (and still employed Gulf co-worker). To some degree these were pity roommates. There were better places for them to rent; certainly better locations. I didn’t care. Nor did they. I was grateful for the help.

I attended the career counselling that Gulf offered as part of my severance package only to have my assigned counsellor suggest I become a Chippendale’s dancer. Seriously! If only that had been the weirdest thing he man said to me during our sessions.

I attempted to get on a radio morning show by promising to donate my first month’s pay to charity if I got a job. The celebrity DJ accepted my offer and agreed to have me on the air. I told everyone I knew to listen to the local rock station on the agreed upon morning. I anxiously practiced my live interview with the radio audience alone in my room for hours the night before. I arrived at the radio station, as directed, to discover the DJ was at home nursing a hangover and nobody else knew I was coming. I never did get on the radio.

Eventually, I would receive two job offers, modest ones, from tiny oil companies nobody had heard of and few ever did. I almost lost those jobs thanks to the negotiating advice that same idiotic counsellor gave me. A flustered mea culpa saved my ass and I did get hired.

That job became the best I’ve ever had and most likely ever will have. I managed to keep my house, my solvency, and my girlfriend. She would move in and the roommates would move out, though not at the same time. She’s now my wife and mother of our two fantastic kids. I even got a decade of that geological career.

I had withstood the harrowing experience I’d twice watched others endure. I had done so, perhaps not gracefully, but with far less struggle than I feared. The change it forced upon me led to some of the most beneficial and memorable periods of my life; a genuine blessing. I started to feel, not quite bulletproof, but certainly immunized to the deleterious effects of such layoffs. Not only had I been exposed to two of these, I’d survived a third during a serious downturn in the commodity cycle while possessing minimal work experience. I’d survived and even flourished. I was fully vaccinated against oil patch ails.

Our Luck Runs Out

Six days ago, almost twenty years to the day after my encounter with the corporate guillotine, my wife lost her job; our family’s only source of income. It didn’t take long to realize my vaccination had failed.

It would be insincere to say my wife’s layoff was a shock. This had long been a real possibility. She too had survived a previous round of layoffs a couple of years ago. Those firings were a monumental change for a previously high-flying, young company. Ever since, continued employment had felt decidedly impermanent.

Significant turmoil both at the company and in the oil industry this past year had made further layoffs all but inevitable. The CEO and founder being dumped was the first pulsing, red warning light that change was coming. The hiring of a new CEO whose prior claim to fame was gutting another previously high-flying oil company in town was the siren. Only an unexpected hostile corporate takeover by a larger competitor postponed the imminent staff cull. And all the takeover would really do is transfer responsibility for the layoffs from existing management to new management. When the hostile suitor inexplicably walked away from their proposed takeover, the blinking lights and alarms only intensified. Sure enough, one month later, the blade finally fell and my wife was on the block when it did.

We were prepared for this. We expected this. A little part of me maybe even hoped for this. And yet, when my wife shared an email announcing layoffs would be happening that very morning that she received while riding transit to work, the reality of it hit me like a boulder dropped from an overpass onto my windshield. I had commented to my wife many times that I hoped they did it quickly if they do plan to do it. I never expected it to be this abrupt.

Within an hour, the termination was official and my wife texted me the news. All those reactions and emotions from twenty years ago flashed over my body like a flaming bar shot spilling over my face. The same fear. The same sorrow. The same panic. The same anger. The same wounded pride. I thought I was immune. At that very moment I discovered I was not. And it wasn’t even me getting sacked.

Sorrows don’t get drowned en masse anymore. Not in 2019 Calgary. This downturn has just been too long and deep for a raucous wake at a nearby pub. The same boxes get filled followed by the same final walk to the elevator bank, but now you simply say a few goodbyes and go home.

We’re in far better financial shape than I was in 1999. We have no mortgage for starters. We have solid savings and my wife’s severance is more substantial than the one I had earned over ten months of work as a twenty-something newbie. We even have roommates already in our house, though it’s unlikely I’ll milk much rent from them, being my children and all.

We will be okay. At least for a while. We’ve done our boy scout best and engage this uncertainty in our life well prepared. But fear is primal and pride, stubborn. We’ve lost our income and my wife lost something she was damn good at. She was a loyal, dedicated, and skilled professional, the very kind corporations clamour to hire and boast of employing. None of which mattered, in the end. I’m sad for her. She deserved better. As did many others.

I’m also beset by guilt, having been a stay-at-home dad for over a decade. I feel like I haven’t pulled my weight, especially these last couple years as the kids grew more independent. Health and circumstances complicated matters, but I didn’t do enough to insulate us from this shock. Surely I, if anyone, should have seen it coming.

Anger Won’t Define Me

It’s this guilt and fear and pride that are conspiring to push forth the most dangerous of the emotions roiling beneath my stolid surface. Anger. Anger has infected this city and this province fomenting an insidious irrationality and toxic selfishness that threatens to destroy otherwise wonderful, generous people. I can understand why. Now more than ever. But I refuse to slither down that resentful, finger-pointing road.

This last, great oil boom died a hard and continuing death. It’s very likely more people will lose their jobs before my wife finds a new one. She may never find one in the industry. I, myself, am literally unemployable in my former profession, having spent too many years away from a job with too many candidates chasing too few positions. It is a dispiriting, frightening situation with no end, never mind a rebound, in sight.

But no single politician is to blame. Not federally, not provincially. Not left, not right. Not even the one with the ghostly name from clashes long ago and a shocking lack of judgement. It’s not Quebec. It’s not First Nations. It’s not even environmental organizations and their mysterious foreign funding. It’s not heavy oil differentials. It’s not proposed regulatory legislation. It’s not even the lack of pipelines to tidewater. It’s all these things and it’s none of them because in the real world things are more complicated than simply pointing your finger at whichever boogeyman or prejudice your tribe holds most dear.

It is so easy to be angry. I can feel it right here, just waiting to explode. I won’t let it. My wife’s job was absolutely fantastic when times were booming. It was a great experience and we benefited tremendously from being a part of it for eight years. We befriended some incredible people and our family leaves with experiences and memories that will stay with us always. I’m sad it came to this kind of end but glad to have been part of it at all.

I don’t know what we will do. My wife will attempt to get a new job, of course. And, yeah, I’ll likely have to try as well, something I whined about recently on this very blog but now feels terrifyingly essential. And impossible. I grew fond of my six and a half hours alone holding down the couch and eating tasty treats as often as I felt was warranted.

I do know what I won’t do. I won’t be donning a yellow vest or driving my banner-festooned SUV to parliament hill. I won’t be ranting irrationally on Twitter or sharing hyperbolic memes on Facebook. I won’t resort to absurd finger pointing or bitterly condemn groups of people, or individuals.

This is life in the patch. In a crazy, complex, evolving world. Be resilient. Be prepared. Be kind. And don’t let fear transform you and anger define you.

P.S. Please hire my wife.

Interesting read. I am also a geologist. For nearly ten years now I have made a go of this career. I have been lucky as I took my fathers advice (he had one of those good careers) and did mud logging and wellsite every time I was laid off. Not the glamor of frontier exploration where I started, but it is an area that has saved me and allowed me to be very employable by companies who want someone who can wear lots of different hats.

You can always mudlog….

Brain: Yes! Yes you can.

Body: You want to what now?

Brain: Do wellsite.

Body: Mmmm …. yeah, I don’t think so. [pulls muscle reaching for carrot stick from fridge crisper]

You are an excellent writer!

Thank you!

This one was tough to read. Throughout my own career I’ve been the manager delivering bad news to respected co-workers and employees. I’ve been the shadowy executive distributing the list of mandated cuts. And, I’ve been on the receiving end of my own terminated position. They all just suck, but the loss of a job when finances are precarious must be worst of all.

I know you and your family will be OK, I’m just hoping the OK part comes along really fast for you.

You’ve had a well-rounded corporate life. :o)